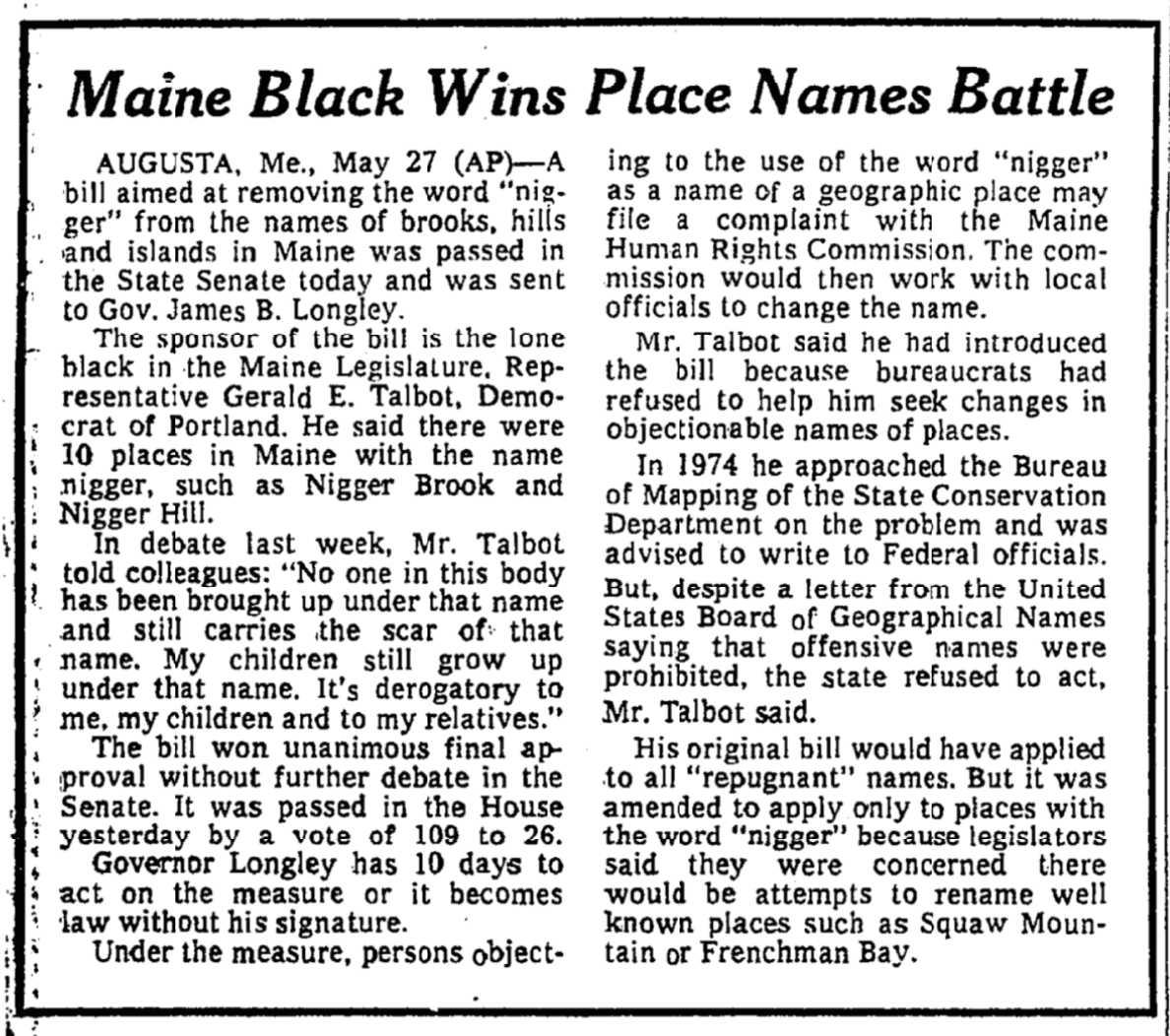

Efforts are underway to remove and replace offensive place names from sites around our country. Maine was ahead of the curve in addressing the issue of offensive place names. In 1977, the state’s first African American state legislator, Representative Gerald E. Talbot, sponsored an “An Act to Prohibit the Use of Offensive Names for Geographic Features and Other Places Within the State of Maine.” When Representative Talbot’s LD 1661 bill was signed into law, the event made national headlines.

With the passage in 2000 of LD 2418, sponsored by Passamaquoddy Tribal Representative Donald Soctomah, the definition of “offensive name” in statute was clarified to include both the “N-word” and the “S-word,” a term that has historically been used as a racist and sexist slur against Indigenous women. Nearly a decade later, it was necessary to further clarify the original law by putting forward LD 797, “An Act To Fully Implement the Legislative Intent in Prohibiting Offensive Place Names,” as a means of prohibiting the use of any derivation of the “S-word” in place names.

Forty-three years after LD 1661 was signed into law, Representative Rachel Talbot Ross learned that her father’s landmark bill had not been effectively enforced. In the summer of 2020, it came to her attention that five Maine islands and several other sites in the state continued to bear offensive names. When this revelation was made public, officials hastened to change the names of three of the islands in question and instructed two other localities to follow suit. But offensive and problematic terms remain inscribed to this day on Maine’s landscapes and maps.

Current Legislation

Place Justice takes its mandate from LD 1934, “Resolve, Changing the Identifying and Reporting Responsibilities and Extending the Reporting Deadline for the Identification of Places in the State with Offensive Names,” which was sponsored by Representative Rachel Talbot Ross and passed on April 12, 2022.

LD 1934 builds on the foundation laid by LD 1591, which entrusted the work of eradicating offensive place names in Maine to the Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry in collaboration with the Permanent Commission. As an extension bill, LD 1934 expands the original research goals and scope of work while shifting responsibility for carrying out its mandate to the Permanent Commission.

This resolve directs the Permanent Commission to:

- Create and operationalize an advisory committee

- Identify additional offensive words and embed them in statute

- Establish a uniform renaming process that it will proactively aid communities in navigating

- Create a means of identifying individuals and entities having benefited from the global economy of enslavement in view of locating places named in their honor

Expanding the scope

Past experience has shown that legislating the eradication of offensive names does not alone ensure implementation, nor does it resolve the underlying issue—namely, that the racism having taken root centuries ago which manifests in hateful or problematic place names has yet to be effectively dismantled. Policy is important, but it is only through sustained community dialogue-across-difference that we can hope to surface, acknowledge, and redress truths of racialized harm and privilege.

Place Justice expands the scope of inquiry beyond what is mandated by LD 1934 to engage communities in a statewide truth-seeking and historical recovery process that asks, Whose memory is visible and celebrated and whose has been erased or misrepresented? How do the politics and practices of public remembrance and forgetting continue to impact communities today?

Considering a wide range of commemorative elements, this collective inquiry invites all those who call Maine home to begin taking active notice of the memoryscape in which we exist and yet have largely come to take for granted.

Memory, like race, is socially constructed. A memoryscape is the commemorative landscape that surrounds us but is often barely noticed. It includes museums, monuments, historical markers, street signs, place names, cemeteries, official narratives, and other forms of remembrance.

The work of Place Justice involves:

- examining naming and other commemorative practices statewide

- identifying racist and offensive place names

- engaging local communities in responding to issues of representation

- inviting community dialogue about the history and meaning of place names and the contours of exclusion and belonging

- organizing listening sessions with impacted groups

- hosting community events

- developing a Place Justice Community Handbook

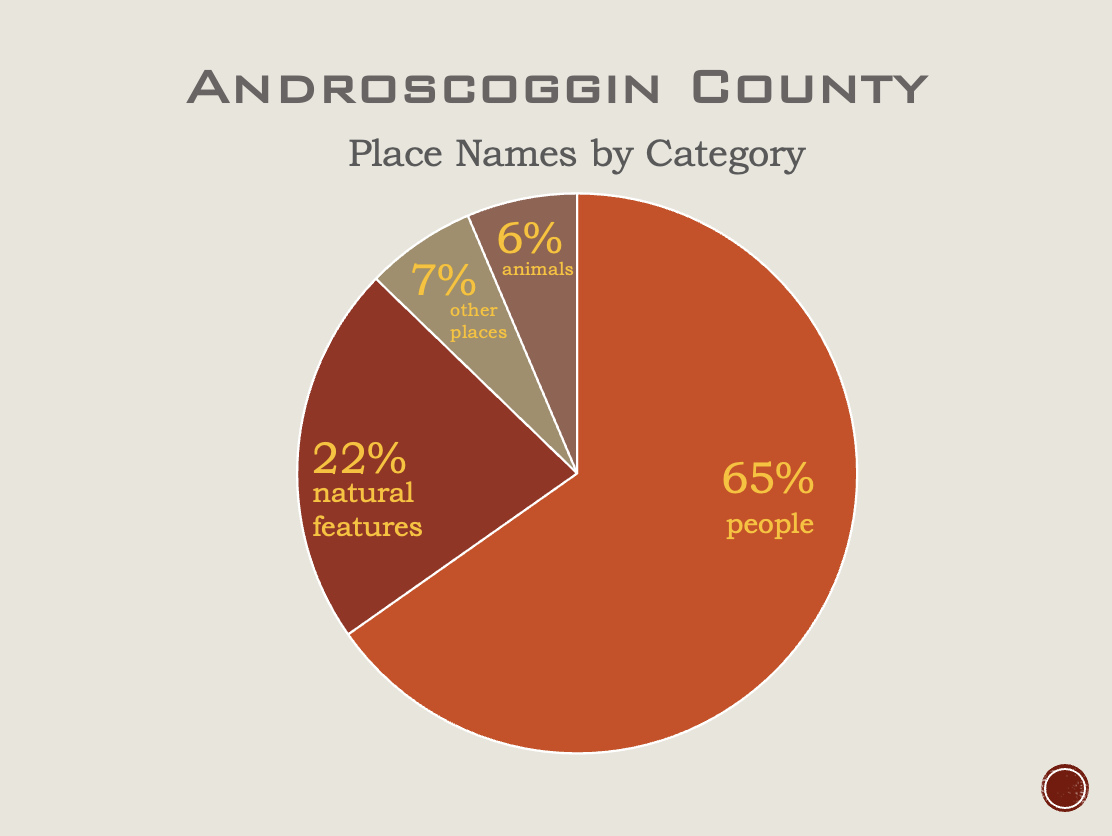

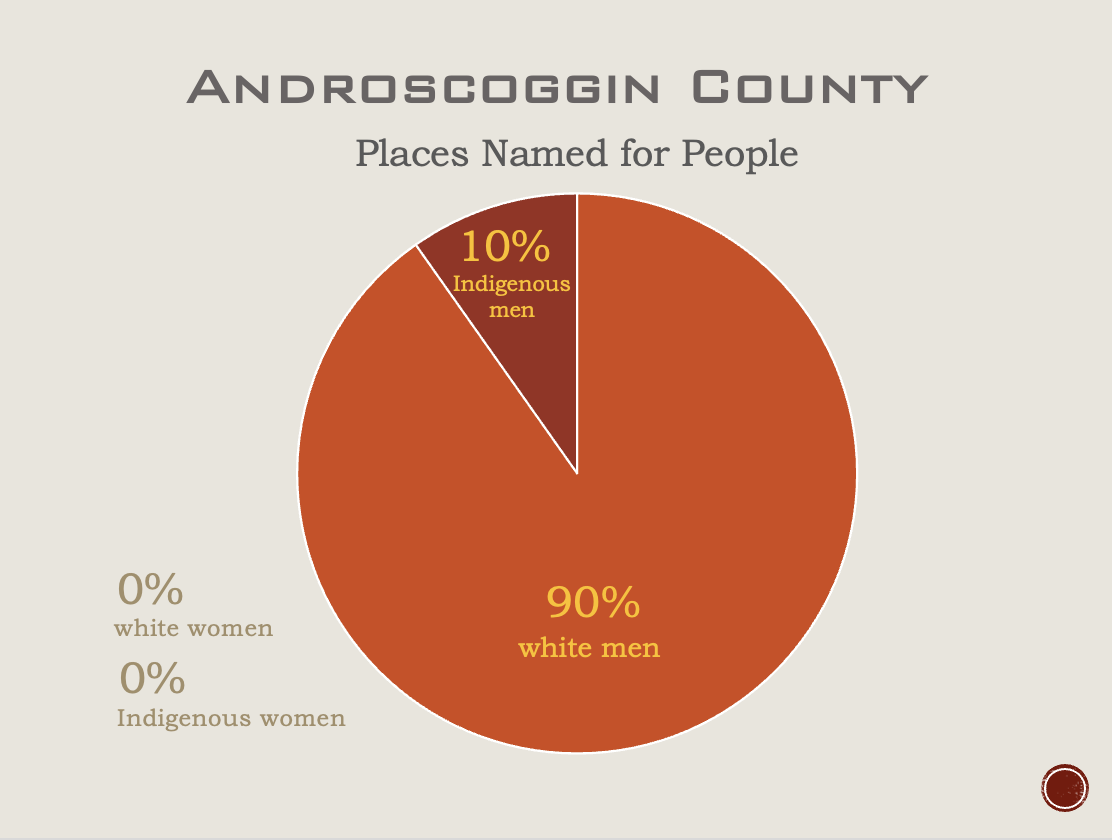

A preliminary analysis of place names in Androscoggin County reveals that 65% of all names commemorate individuals. Of those, 90% of place names honor of white men, most of them settler colonialists.