Social Drivers of Health Dashboard

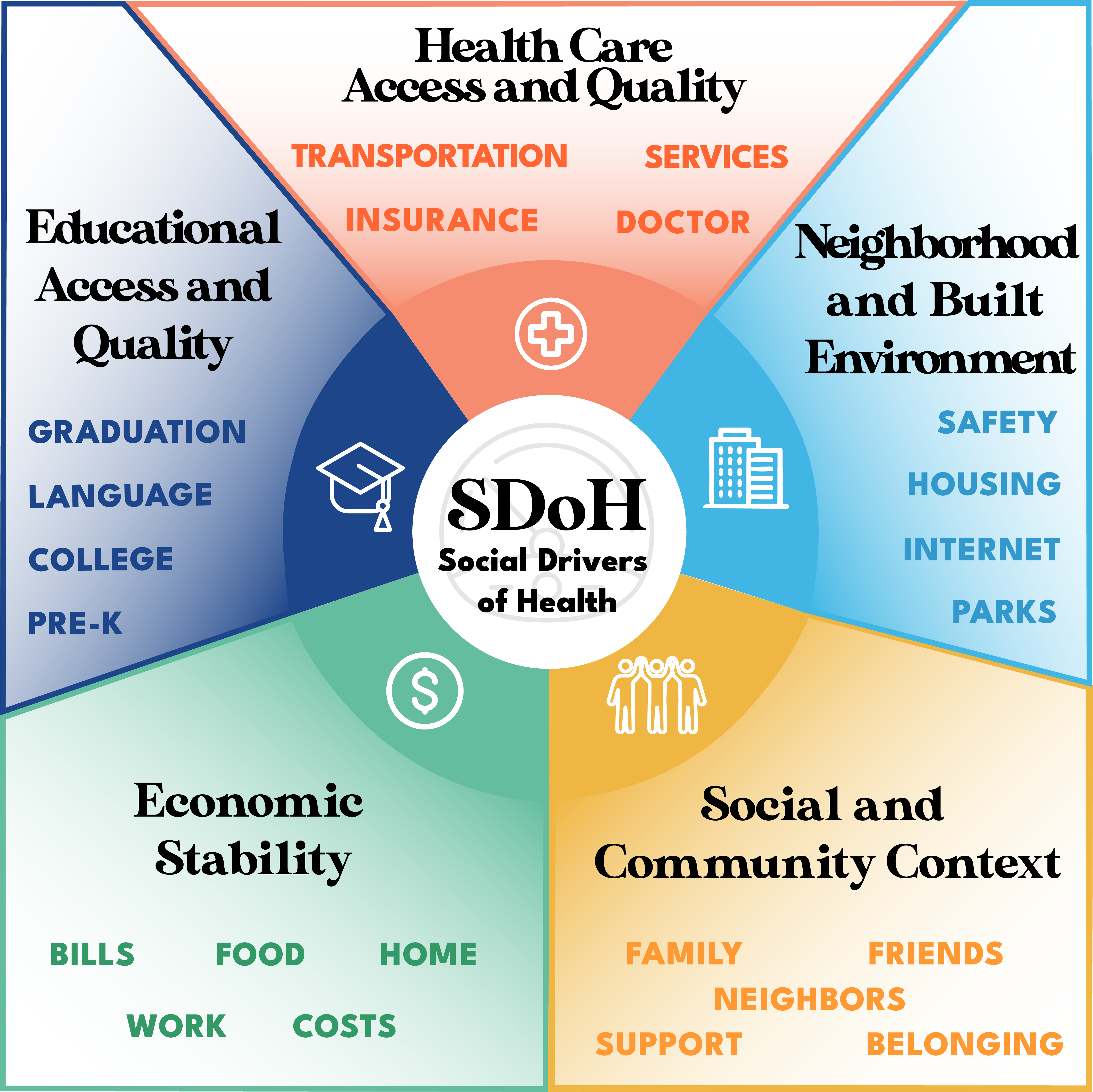

| Figure 1. Health outcomes are tied to our social environment, including our access to fresh food, education, work, and community connections. |

|---|

|

The SDOH framework was first established in the 1970s as a way to help researchers and medical professionals better understand why disparities persist in health outcomes at the population level. They defined a number of factors that drive health disparities—things like income, housing, education, and whether people are safe and supported in their communities. The SDOH framework also showed that those situations and circumstances are not random across the landscape, but are shaped by systems that advantage some groups and disadvantage others—based on education, job opportunities, gender, race, and more (See Figure 1). Since then, public health professionals have begun to focus increased attention on interventions at the social and structural levels as a means of enhancing health equity and positive health outcomes.

What are the Social Drivers of Health?

While many factors shape health and well-being in our communities, the United States Department of Health and Human Services breaks these down into five primary categories, known as the Social Drivers of Health:

Economic Stability

Steady work and income, safe housing, and enough food are basic building blocks of health. When people can meet the basic needs of keeping a roof over their head, meals on the table, and bills paid, they’re more likely to stay healthy and get the care they need.

Educational Access and Quality

Education opens doors to better-paying jobs with benefits – including healthcare – and safer working conditions. It also makes it easier to understand medical information, talk to providers, and make informed decisions about your health.

Health Care Access and Quality

Many people struggle to afford care or don’t have a primary care provider (PCP) they can go to. Without health insurance and affordable deductibles, people are often forced to skip preventative care, delay treatment, or miss out on lifesaving services like cancer screenings.

Neighborhood and Built Environment

Where we live affects our health—whether our homes are safe, whether there’s clean air and water, whether we can walk to a park or buy groceries nearby. Stress from unsafe or unhealthy surroundings can take a serious toll, while access to green space and essential services supports mental and physical health.

Social and Community Context

Strong social ties—like friendships, family, or community groups—make a big difference. Feeling connected helps people cope with stress, avoid isolation, and access support like transportation, food, or care. When people are engaged in their communities, it creates shared expectations, mutual support, and better health for everyone.

Racial Disparities and SDOH

Health disparities across race are not the result of biology, they’re the result of social structures and public policy. Exclusionary systems have led to higher rates of illness, maternal mortality, and chronic conditions like cancer and heart disease among communities of color.

Some of the harm comes from discrimination and lack of access in the health care system itself. But the roots go deeper – into unequal schools, underpaid jobs, unsafe housing, and food insecurity. These are the outcomes of long-standing systems: colonization, redlining, forced removal, segregation, over-incarceration, and ongoing underinvestment in Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color.

The Social Drivers of Health framework helps make these connections visible. It shows how systemic racism shows up in everyday life—and how we can begin to change it. And while the specific histories are different, we also see some of these same system failures play out in under-resourced rural communities. When we shift policy and resources to meet people’s real needs, we improve health outcomes for everyone.

| Additional Resources on SDOH and Systemic and Structural Racism |

|---|

| Castle, B. et al. (2018). Public Health’s Approach to Systemic Racism: a Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 6: 27-36. |

| Gee, G. & Ford, C. (2011). Structural Racism and Health Inequalities: Old Issues, New Directions. Du Bois Review, 8(1): 115-132. |

| Javied, Z. et al. (2022). Race, Racism, and Cardiovascular Health: Applying a Social Determinants of Health Framework to Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 15(1): 72-86. |

| Paradies, Y. (2006). Defining, Conceptualizing and Characterizing Racism in Health Research. Critical Public Health, 16(2): 143–157. |

| Paradies, Y. et al. (2015). Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE, 10(9): 1-48. |

Interactive SDOH Dashboard

Understanding SDOH requires that we have access to data at and across multiple scales. Below, we have compiled publicly available data on indicators for each of the areas of SDOH outlined above where data was available, broken down within Maine by race, and as a comparison between Maine and the national average. Tabs at the top of the screen will help you navigate between different indicators. Most of the data in this dashboard originates from the American Community Survey, but if you want more information, click here to see our indicator spreadsheet. This dashboard is updated annually and new indicators will be added over time.

A note on these indicators: Because of the limited availability of data - especially data capable of being disaggregated by race in Maine - many of the indicators here are “proxy variables”—small snapshots that help us understand big, complex realities like economic stability or housing insecurity. For some of the data presented here, better proxies may exist at the national level, but could not be included for Maine. Data limitations in Maine, especially around experiences of communities of color, make it harder to design the services people need and to hold systems accountable. Because of these limitations, information in this database should be considered a starting point for further research rather than “proof” that disparities do or do not exist within particular communities. Where possible, we have added additional explanatory information that can be viewed by hovering over charts, maps, and graphics. We hope this helps to provide context to the data, offer transparency around our limitations, and provoke ideas for further inquiry.